Our first debate of the year focuses on whether or not TV surpassed film in 2016. What do you think? Read our Movie Parliament ministers debate it below and then cast your vote!

Proposition

Michael Dalton, Prime Minister:

The two most emotional reactions I had to something on a screen last year both came from Netflix. The first was the punch line at the end of Bojack Horseman’s amazing episode, ‘Fish out of Water’ which played like a slapstick Saturday morning cartoon meets a Lost In Translation-esque existential drama. The realization that Bojack has at the end of that episode, and the final line before it cuts to black, had me laughing longer and harder than any comedy I saw on the big screen. Secondly, was the episode, 'San Junipero' from the third season of Charlie Brooker’s superb anthology show, 'Black Mirror'. Breaking from the dark and cynical Black Mirror mold, San Junipero would have been my favourite film of 2016 had it been released in cinemas. Its bittersweet conclusion left me in tears and thinking about the big questions like the best of sci-fi does. The only film last year that came close to it, both thematically and emotionally, was Denis Villeneuve’s, 'Arrival'. It is also hard to escape the fact that, aside from perhaps Captain America: Civil War, the biggest and most anticipated pieces of entertainment were on the small screen. Game of Thrones’ Battle of the Bastards matched anything on the big screen for scale, whilst I don’t think any summer blockbuster had quite the cultural impact that Stranger Things enjoyed. Like it or not, TV has become just as cinematic as cinema and it’s where the real high-quality storytelling resided in 2016.

The two most emotional reactions I had to something on a screen last year both came from Netflix. The first was the punch line at the end of Bojack Horseman’s amazing episode, ‘Fish out of Water’ which played like a slapstick Saturday morning cartoon meets a Lost In Translation-esque existential drama. The realization that Bojack has at the end of that episode, and the final line before it cuts to black, had me laughing longer and harder than any comedy I saw on the big screen. Secondly, was the episode, 'San Junipero' from the third season of Charlie Brooker’s superb anthology show, 'Black Mirror'. Breaking from the dark and cynical Black Mirror mold, San Junipero would have been my favourite film of 2016 had it been released in cinemas. Its bittersweet conclusion left me in tears and thinking about the big questions like the best of sci-fi does. The only film last year that came close to it, both thematically and emotionally, was Denis Villeneuve’s, 'Arrival'. It is also hard to escape the fact that, aside from perhaps Captain America: Civil War, the biggest and most anticipated pieces of entertainment were on the small screen. Game of Thrones’ Battle of the Bastards matched anything on the big screen for scale, whilst I don’t think any summer blockbuster had quite the cultural impact that Stranger Things enjoyed. Like it or not, TV has become just as cinematic as cinema and it’s where the real high-quality storytelling resided in 2016.

Opposition

Arnaud Trouve, Minister for Foreign Affairs

If you ask me what cinematic experience I was most anticipating in late December, I would not say “Rogue One”, but the Christmas Special of “Sense8”, the Netflix series by the Wachowski sisters. While FX’s “The People vs OJ Simpson” was the best courtroom drama I’ve seen in a long time, and many shots of cinematic brilliance were also to be found in Paolo’s Sorrentino’s mini-series “The Young Pope”.

2016’s TV offerings were mostly as diverse and original as the cinematic landscape seemed dull and mundane. Why is it that so many youngsters (I’m still including myself) are more prone to binge-watch a 10-hour series than sit through a full 100-minute drama?

Maybe the fault lies in a specific type of motion picture, massively designed to attract people to the theatre: the blockbuster. With one of its most disappointing summers ever in terms of quality, Hollywood’s tendency to rely on emotionless spectacle and recycled brands was glaring. In a globalized world, everything seems tailor-made to satisfy everyone, and especially the Asian market. “Universe-building” has become a synonym for “money-grabbing”. And while those films still cash in big bucks during their opening weekends, they fail to intrigue spectators and tease them to come back for more daring spectacle. Thus, the (not less formatted) “Oscar movie” opens only in selected cities for a couple of weeks; award ceremonies embrace those films that virtually no one saw, and the cycle starts again.

But let’s not blame it all on Hollywood: the same scenario is playing here in France. Among the 10 highest-grossing French films at our yearly box-office, only two are guaranteed to get nominated for a César. “Chocolat” is a biopic of Rafael Padilla, the first Black clown and thus first Black artist in France at the beginning of the 20th century. Starring Omar Sy, the film earned 2 million admissions, which is good but hard to call a big hit. The other is “Médecin de campagne” (Country Doctor), a dramedy whose rural setting certainly pleased an older category of the population.

A little lower on the ranking is “The Odyssey”, the biopic of Jacques-Yves Cousteau by Jérôme Salle (Largo Winch), which surprisingly underwhelmed. And let’s thank Xavier Dolan for shooting in French: “It’s Not the End of the World” is the fourth and last “serious contender” to even sell more than 1 million admissions, a famous threshold that used to be a minimum for standard quality and popular films. (Our population is around 66 million). The fact is that all remaining French films at the top of box-office are comedies, most of them quite dumb and won’t sell well to foreign markets.

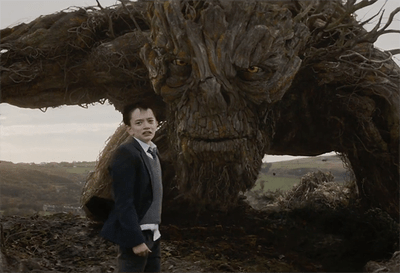

But all is not lost. “A Monster Calls” is still the highest-grossing film of the year in Spain, a country that is not afraid of fantasy & science-fiction (I’m looking at you, France), and the home of many brilliant directors (Bayona, Amenábar). China’s romantic comedy “The Mermaid” is a half-billion dollar monster hit, and another proof of the genius of Stephen Chow (Shaolin Soccer). South Korea put “Train to Busan” and “The Wailing” at #1 and #6 respectively, and those are not exactly family-friendly comedies. Both having screened in Cannes, “Busan” is a zombie flick and “Wailing” a thriller dark enough to make “Seven” look like “Zoolander”.

My point is that, with enough promotion and confidence in your audience, cinema can still be a place where we experience bold and unforgettable moments. “Netflix and chill” ? I’d rather hear a whole packed theatre laugh during the end credits of “Zootopia”, or eavesdrop on my two elderly neighbors who thought during the entire film that “Manchester by the Sea” was taking place in England.

If you ask me what cinematic experience I was most anticipating in late December, I would not say “Rogue One”, but the Christmas Special of “Sense8”, the Netflix series by the Wachowski sisters. While FX’s “The People vs OJ Simpson” was the best courtroom drama I’ve seen in a long time, and many shots of cinematic brilliance were also to be found in Paolo’s Sorrentino’s mini-series “The Young Pope”.

2016’s TV offerings were mostly as diverse and original as the cinematic landscape seemed dull and mundane. Why is it that so many youngsters (I’m still including myself) are more prone to binge-watch a 10-hour series than sit through a full 100-minute drama?

Maybe the fault lies in a specific type of motion picture, massively designed to attract people to the theatre: the blockbuster. With one of its most disappointing summers ever in terms of quality, Hollywood’s tendency to rely on emotionless spectacle and recycled brands was glaring. In a globalized world, everything seems tailor-made to satisfy everyone, and especially the Asian market. “Universe-building” has become a synonym for “money-grabbing”. And while those films still cash in big bucks during their opening weekends, they fail to intrigue spectators and tease them to come back for more daring spectacle. Thus, the (not less formatted) “Oscar movie” opens only in selected cities for a couple of weeks; award ceremonies embrace those films that virtually no one saw, and the cycle starts again.

But let’s not blame it all on Hollywood: the same scenario is playing here in France. Among the 10 highest-grossing French films at our yearly box-office, only two are guaranteed to get nominated for a César. “Chocolat” is a biopic of Rafael Padilla, the first Black clown and thus first Black artist in France at the beginning of the 20th century. Starring Omar Sy, the film earned 2 million admissions, which is good but hard to call a big hit. The other is “Médecin de campagne” (Country Doctor), a dramedy whose rural setting certainly pleased an older category of the population.

A little lower on the ranking is “The Odyssey”, the biopic of Jacques-Yves Cousteau by Jérôme Salle (Largo Winch), which surprisingly underwhelmed. And let’s thank Xavier Dolan for shooting in French: “It’s Not the End of the World” is the fourth and last “serious contender” to even sell more than 1 million admissions, a famous threshold that used to be a minimum for standard quality and popular films. (Our population is around 66 million). The fact is that all remaining French films at the top of box-office are comedies, most of them quite dumb and won’t sell well to foreign markets.

But all is not lost. “A Monster Calls” is still the highest-grossing film of the year in Spain, a country that is not afraid of fantasy & science-fiction (I’m looking at you, France), and the home of many brilliant directors (Bayona, Amenábar). China’s romantic comedy “The Mermaid” is a half-billion dollar monster hit, and another proof of the genius of Stephen Chow (Shaolin Soccer). South Korea put “Train to Busan” and “The Wailing” at #1 and #6 respectively, and those are not exactly family-friendly comedies. Both having screened in Cannes, “Busan” is a zombie flick and “Wailing” a thriller dark enough to make “Seven” look like “Zoolander”.

My point is that, with enough promotion and confidence in your audience, cinema can still be a place where we experience bold and unforgettable moments. “Netflix and chill” ? I’d rather hear a whole packed theatre laugh during the end credits of “Zootopia”, or eavesdrop on my two elderly neighbors who thought during the entire film that “Manchester by the Sea” was taking place in England.

Proposition

Victor Escobar https://twitter.com/VicAEsco

As with the end of every year, I find that I’ve missed out on a lot of cinema. I haven’t seen Moonlight, Manchester by the Sea or Jackie. I’m sure I will in the following months but this is why I wait until Oscar weekend to release my top ten.

I’ve missed out because I’m getting older and getting older means responsibilities and boring stuff but tonight I find myself with enough spare time to catch one of 2016’s offerings. I’m currently scrolling through 35 director’s favorite films of 2016 on Indiewire (http://www.indiewire.com/2016/12/directors-2016-favorite-movies-tv-shows-jonathan-demme-paul-feig-marielle-heller-sam-esmail-david-lowery-jennifer-kent-1201763198/) for inspiration.

Sure, Moonlight and Arrival and La La Land appear on several but the most fascinating and inspired choices are television programs. Notable programs that appear multiple times include Horace and Pete, Atlanta, Westworld, Stranger Things, and the is-it-or-is-it-not-a-movie O.J. Simpson: Made in America. Hell, even Hilary Clinton’s performance in the three presidential debates made it on to a list.

At this point, the line between television and cinema has blurred. I used to think that the excuse of something warranting your need to actually go out to a cinema was a poor one but I bothered through every lackluster film that was released this summer when I could’ve just stayed home to watch Stranger Things or Black Mirror.

Ironically, the reason why television can now be mentioned in the same breath as film is because our programming looks and feels like a movie. In some sense, each new shared universe that comes out is what our television used to be.

As of lately, it feels like the effort is not there in major studio productions. Everyone is clamoring for the next billion-dollar film at the sacrifice of what truly resonates: story. I feel that today’s storytellers are flocking to the medium of television because of the creative freedom this renaissance has allowed. Television has become a far more intellectually stimulating and rewarding affair. Our characters now live in a morally gray area and we’re no longer required to go through ten seasons of a program, allowing A-list stars, directors, and writers to latch themselves onto a project.

Its downfall may be in it’s proliferation. Alternative services such as Neflix and Hulu are the reason why creators now find themselves with more freedom but it also means that the audience is smaller. I didn’t have time to make it to every film this year and I most certainly did not have time to catch every piece of television that was praised.

There’s no doubt that we’re currently in the middle of the golden age of television. And we’re in a golden age because television is finally as good as the movies are, except it’s much more convenient to stay at home in your underwear than put on a pair of jeans and pay $15 for the next episode in the Marvel universe.

As with the end of every year, I find that I’ve missed out on a lot of cinema. I haven’t seen Moonlight, Manchester by the Sea or Jackie. I’m sure I will in the following months but this is why I wait until Oscar weekend to release my top ten.

I’ve missed out because I’m getting older and getting older means responsibilities and boring stuff but tonight I find myself with enough spare time to catch one of 2016’s offerings. I’m currently scrolling through 35 director’s favorite films of 2016 on Indiewire (http://www.indiewire.com/2016/12/directors-2016-favorite-movies-tv-shows-jonathan-demme-paul-feig-marielle-heller-sam-esmail-david-lowery-jennifer-kent-1201763198/) for inspiration.

Sure, Moonlight and Arrival and La La Land appear on several but the most fascinating and inspired choices are television programs. Notable programs that appear multiple times include Horace and Pete, Atlanta, Westworld, Stranger Things, and the is-it-or-is-it-not-a-movie O.J. Simpson: Made in America. Hell, even Hilary Clinton’s performance in the three presidential debates made it on to a list.

At this point, the line between television and cinema has blurred. I used to think that the excuse of something warranting your need to actually go out to a cinema was a poor one but I bothered through every lackluster film that was released this summer when I could’ve just stayed home to watch Stranger Things or Black Mirror.

Ironically, the reason why television can now be mentioned in the same breath as film is because our programming looks and feels like a movie. In some sense, each new shared universe that comes out is what our television used to be.

As of lately, it feels like the effort is not there in major studio productions. Everyone is clamoring for the next billion-dollar film at the sacrifice of what truly resonates: story. I feel that today’s storytellers are flocking to the medium of television because of the creative freedom this renaissance has allowed. Television has become a far more intellectually stimulating and rewarding affair. Our characters now live in a morally gray area and we’re no longer required to go through ten seasons of a program, allowing A-list stars, directors, and writers to latch themselves onto a project.

Its downfall may be in it’s proliferation. Alternative services such as Neflix and Hulu are the reason why creators now find themselves with more freedom but it also means that the audience is smaller. I didn’t have time to make it to every film this year and I most certainly did not have time to catch every piece of television that was praised.

There’s no doubt that we’re currently in the middle of the golden age of television. And we’re in a golden age because television is finally as good as the movies are, except it’s much more convenient to stay at home in your underwear than put on a pair of jeans and pay $15 for the next episode in the Marvel universe.

Opposition

Leonhard Balk, Minister for History

If there is one thing I have come to realise about the TV and film landscape this year, it is that the Marvel Cinematic Universe has become a scourge upon both industries. What was once referred to as `Sequelitis´ has now evolved into `universe-building´ (we still need a medical term). Both describe similar symptoms of safe and uninspired studio decision-making, but the latter has become a far more invasive phenomenon, as it impacts on story structure, narrative cohesion and, finally, the emotional pay-off for each individual film. We all know about this current trend in film; it is, of course, most visible with superhero blockbusters. Outside of DC and Marvel, “The Mummy”, with its ambitions of becoming the first instalment in Universals new monster universe, is probably the most visible first step towards a non-superhero universe. I would argue that the “Star Wars” franchise has also been infected with this virus, as “Rogue One” represents a move away from the known saga towards a broader universe of films.

But this thinking of connecting films and characters, of stretching a story to contain multiple climaxes and set-ups, affects TV too. To me, universe-building is all about the fear of letting go. A fear of telling a self-contained, self-reliant story, of celebrating success with a film, and then just leaving it alone. Instead, all remaining story potential must be mined, all gaps filled and questions answered. This is nothing new, as this thinking has always made sense from a studio perspective. However, the reason I bring all this up, is that we are now living in a new age of seemingly infinite content and availability. We still haven’t realized the full impact that `binge-watching´ has/will have on our media landscape. Last year, FX’s CEO John Landgraf pronounced that we are likely to reach peak TV in 2016 or 2017 and that the following years would show a decline in new original programming. His pronouncement rings true, at least for me, when we look back at all the shows we watched/missed/meant to watch/stopped watching this year. I don’t know what I’d do if someone were to ask me to do an end of year recap of 2016’s TV offerings. I just started sweating at the thought of it.

It’s easy to lay the blame on the many freshman series entering an already over-saturated market. You can blame network channels branching out into original programming (History Channel, Cinemaxx, A&E…) or various streaming services entering the market (Netflix, Amazon, Hulu & Yahoo Screen), but should we really fault these outlets for creating new content? What I find more troubling, is that, as overall output grows, shows are still being stretched to run multiple seasons. The nature of getting `hooked´ on a show and binging it, for me, goes against returning to said show a year later, in hopes of getting re-hooked. In other words: there are too many shows out there that have outstayed their welcome. People watch them out of a sense of duty (maybe even a fear of missing out), in order to finally reach some sort of closure for something, which they naively started watching five years ago.

2016’s unique freshman shows, like “Stranger Things”, “The Crown”, “Westworld” & “Atlanta”, should be proof that viewers are responding well to new ideas and are looking to get hooked, for a limited time. But I fear TV executives are learning all the wrong things from these successes and are still looking for ways to renew and recreate what should be left alone. Anthology shows like “American Horror Story”, “Fargo” and, yes, “True Detective” have found a nice way of side-stepping this problem. They manage to tell a satisfying, self-contained story over the course of a single season, while still retaining their show’s fan base. This is also why people are responding so well to mini-series like “The People vs. OJ Simpson,” “Horace and Pete”, “The Night of” and “The Night Manager”.

My point is that, while the film landscape allows for the selfish expansion of movie universes, there is simply no space in TV for most shows to keep expanding and hanging on in this way. Executives will have to start making bold creative choices to secure their network’s/service’s place in this new age of supposed `Quality TV´. For, as I see it, this year was about 10% quality and 90% filler.

If there is one thing I have come to realise about the TV and film landscape this year, it is that the Marvel Cinematic Universe has become a scourge upon both industries. What was once referred to as `Sequelitis´ has now evolved into `universe-building´ (we still need a medical term). Both describe similar symptoms of safe and uninspired studio decision-making, but the latter has become a far more invasive phenomenon, as it impacts on story structure, narrative cohesion and, finally, the emotional pay-off for each individual film. We all know about this current trend in film; it is, of course, most visible with superhero blockbusters. Outside of DC and Marvel, “The Mummy”, with its ambitions of becoming the first instalment in Universals new monster universe, is probably the most visible first step towards a non-superhero universe. I would argue that the “Star Wars” franchise has also been infected with this virus, as “Rogue One” represents a move away from the known saga towards a broader universe of films.

But this thinking of connecting films and characters, of stretching a story to contain multiple climaxes and set-ups, affects TV too. To me, universe-building is all about the fear of letting go. A fear of telling a self-contained, self-reliant story, of celebrating success with a film, and then just leaving it alone. Instead, all remaining story potential must be mined, all gaps filled and questions answered. This is nothing new, as this thinking has always made sense from a studio perspective. However, the reason I bring all this up, is that we are now living in a new age of seemingly infinite content and availability. We still haven’t realized the full impact that `binge-watching´ has/will have on our media landscape. Last year, FX’s CEO John Landgraf pronounced that we are likely to reach peak TV in 2016 or 2017 and that the following years would show a decline in new original programming. His pronouncement rings true, at least for me, when we look back at all the shows we watched/missed/meant to watch/stopped watching this year. I don’t know what I’d do if someone were to ask me to do an end of year recap of 2016’s TV offerings. I just started sweating at the thought of it.

It’s easy to lay the blame on the many freshman series entering an already over-saturated market. You can blame network channels branching out into original programming (History Channel, Cinemaxx, A&E…) or various streaming services entering the market (Netflix, Amazon, Hulu & Yahoo Screen), but should we really fault these outlets for creating new content? What I find more troubling, is that, as overall output grows, shows are still being stretched to run multiple seasons. The nature of getting `hooked´ on a show and binging it, for me, goes against returning to said show a year later, in hopes of getting re-hooked. In other words: there are too many shows out there that have outstayed their welcome. People watch them out of a sense of duty (maybe even a fear of missing out), in order to finally reach some sort of closure for something, which they naively started watching five years ago.

2016’s unique freshman shows, like “Stranger Things”, “The Crown”, “Westworld” & “Atlanta”, should be proof that viewers are responding well to new ideas and are looking to get hooked, for a limited time. But I fear TV executives are learning all the wrong things from these successes and are still looking for ways to renew and recreate what should be left alone. Anthology shows like “American Horror Story”, “Fargo” and, yes, “True Detective” have found a nice way of side-stepping this problem. They manage to tell a satisfying, self-contained story over the course of a single season, while still retaining their show’s fan base. This is also why people are responding so well to mini-series like “The People vs. OJ Simpson,” “Horace and Pete”, “The Night of” and “The Night Manager”.

My point is that, while the film landscape allows for the selfish expansion of movie universes, there is simply no space in TV for most shows to keep expanding and hanging on in this way. Executives will have to start making bold creative choices to secure their network’s/service’s place in this new age of supposed `Quality TV´. For, as I see it, this year was about 10% quality and 90% filler.

Closing Remarks

What do you think? Has TV eclipsed film? Has ‘universe-building’ ruined cinema? Can the cinematic experience ever be beaten? Have we reached peak TV? Give us your thoughts in the comments below and let us know whether you agree with the proposition or opposition.

In 2016 TV Was Better Than Film

RSS Feed

RSS Feed